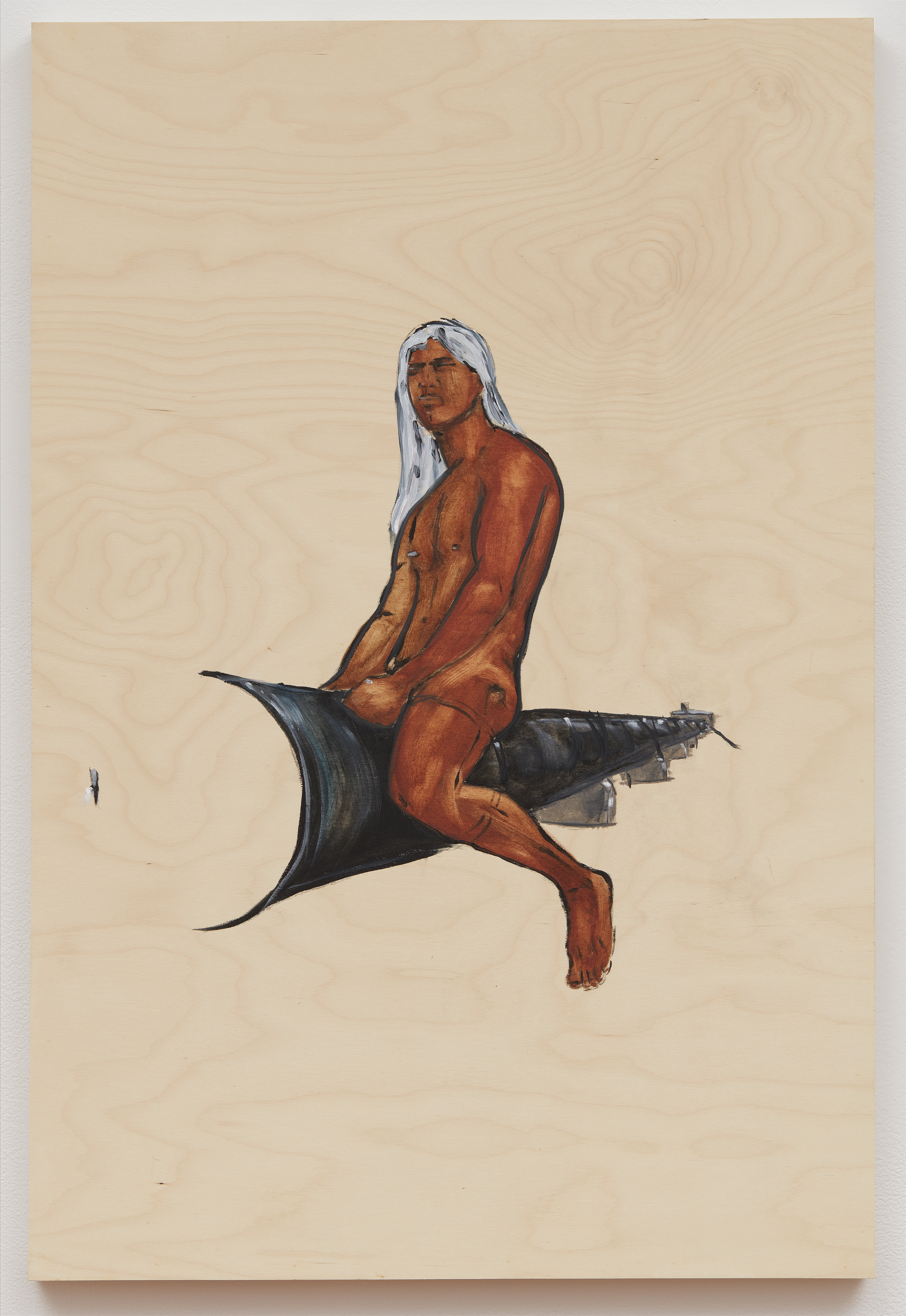

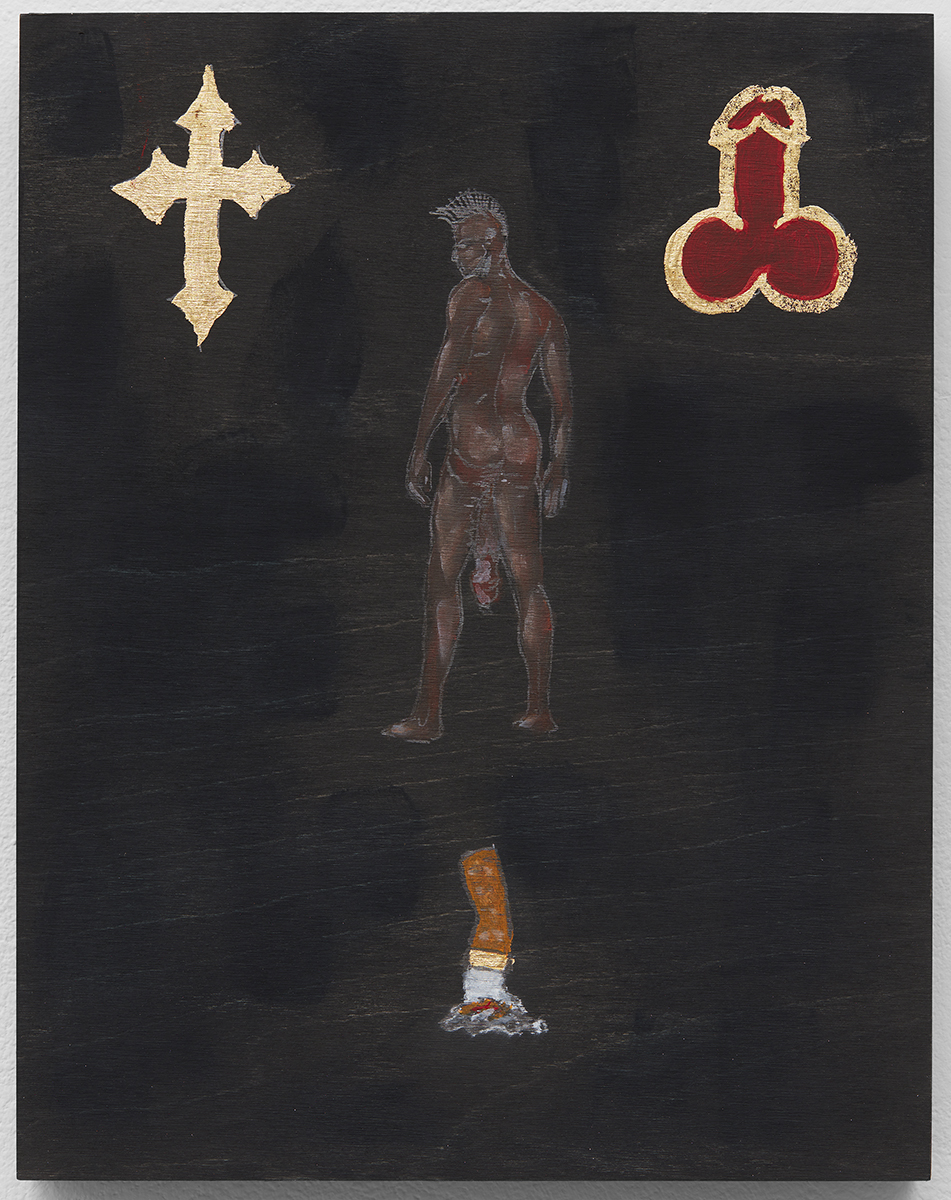

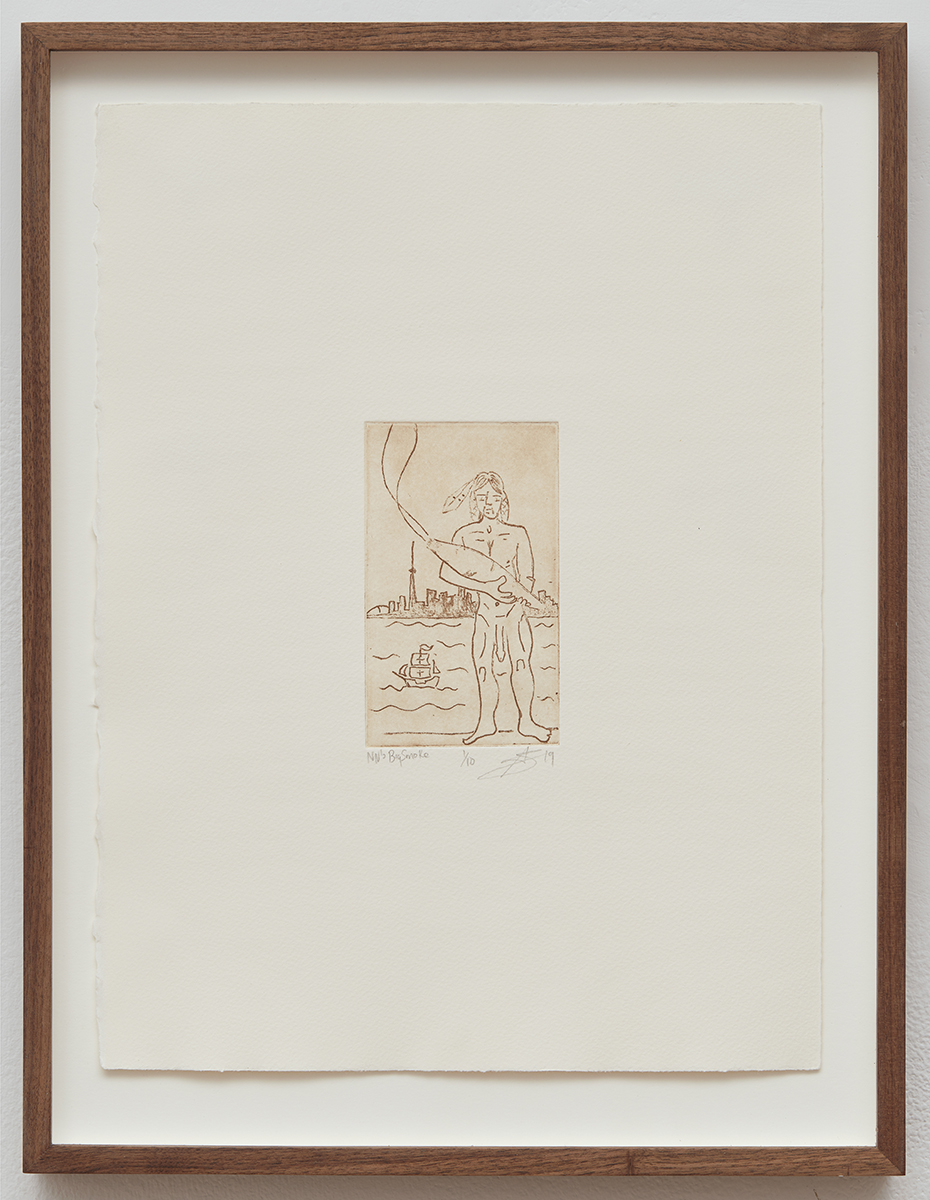

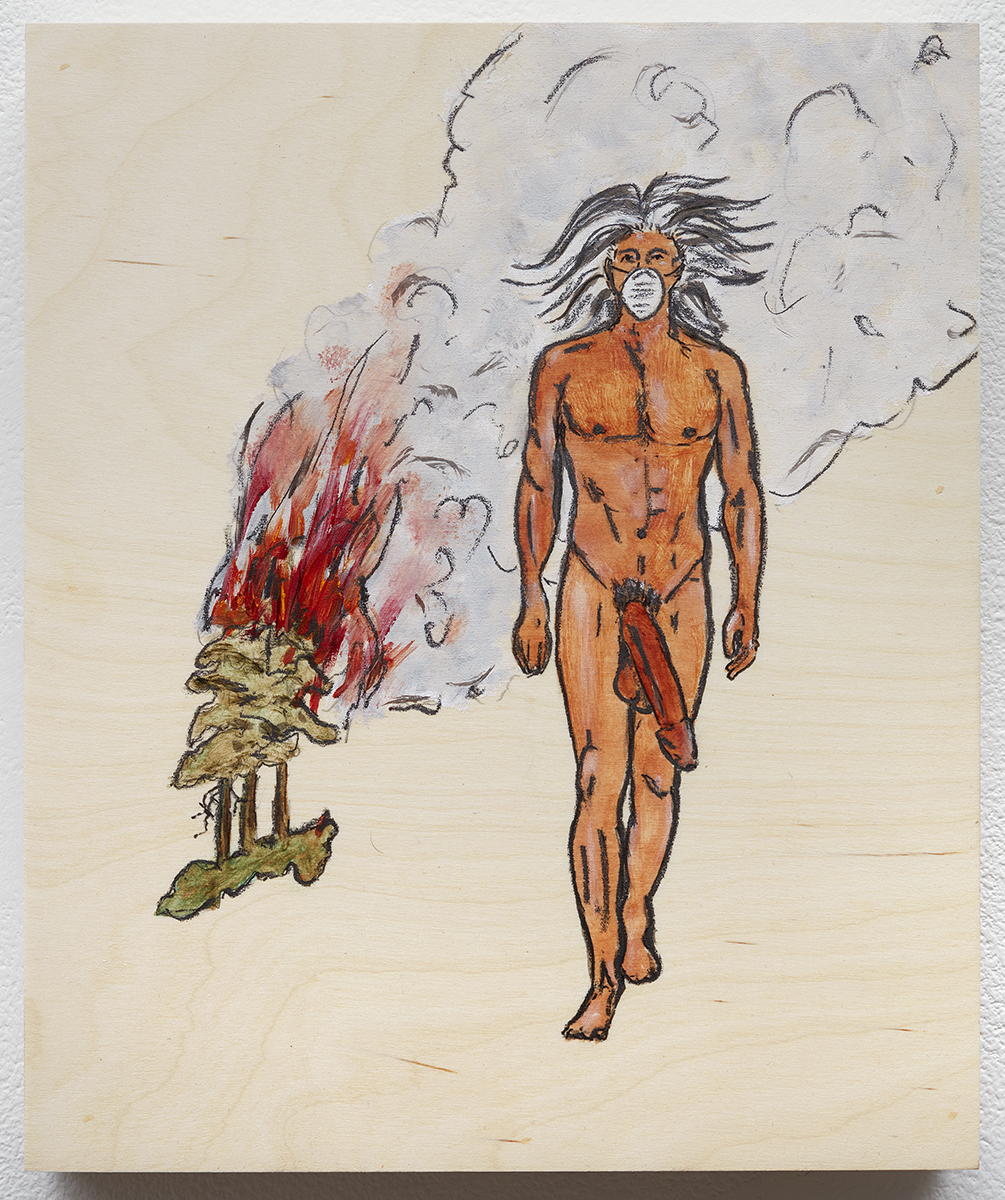

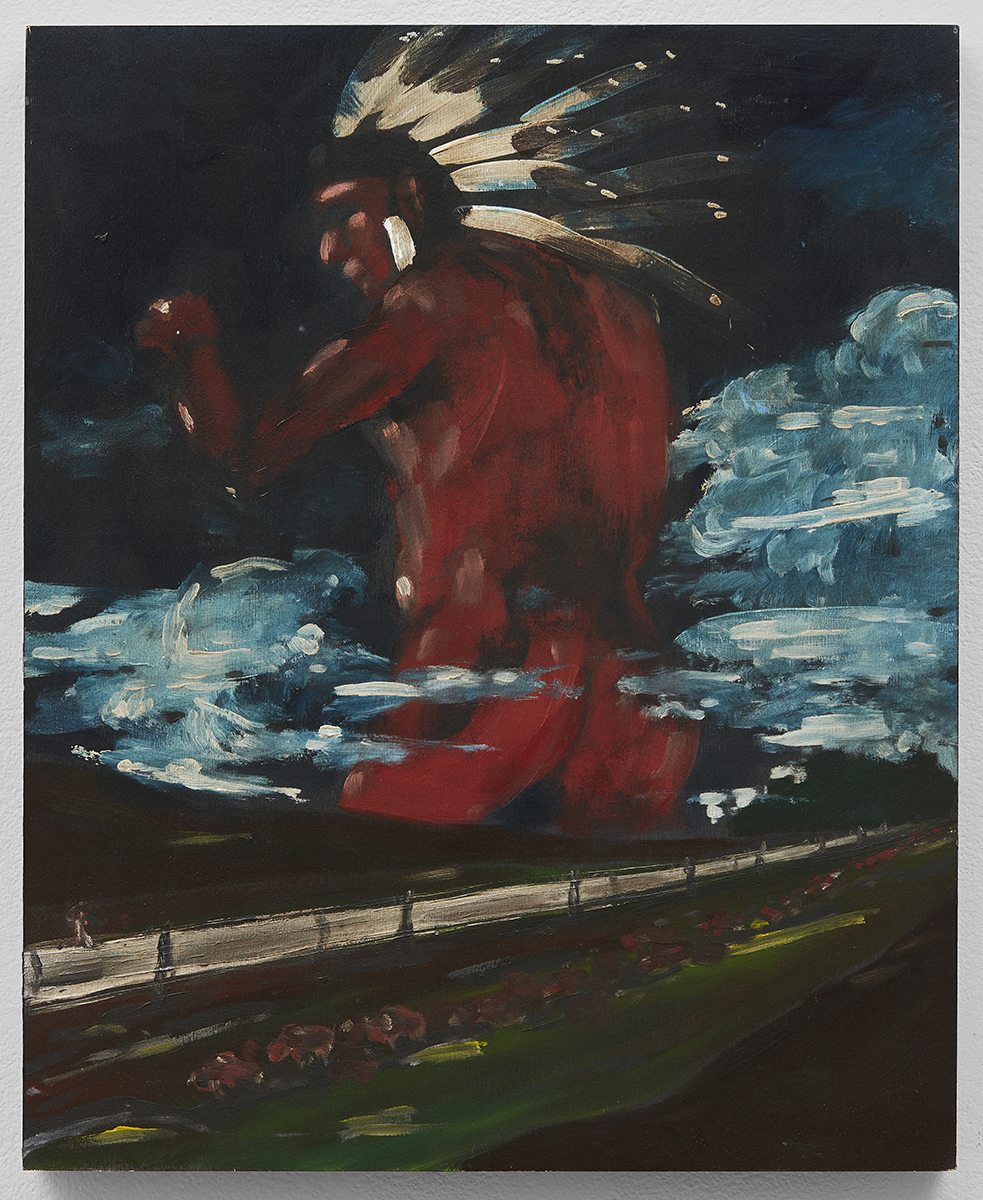

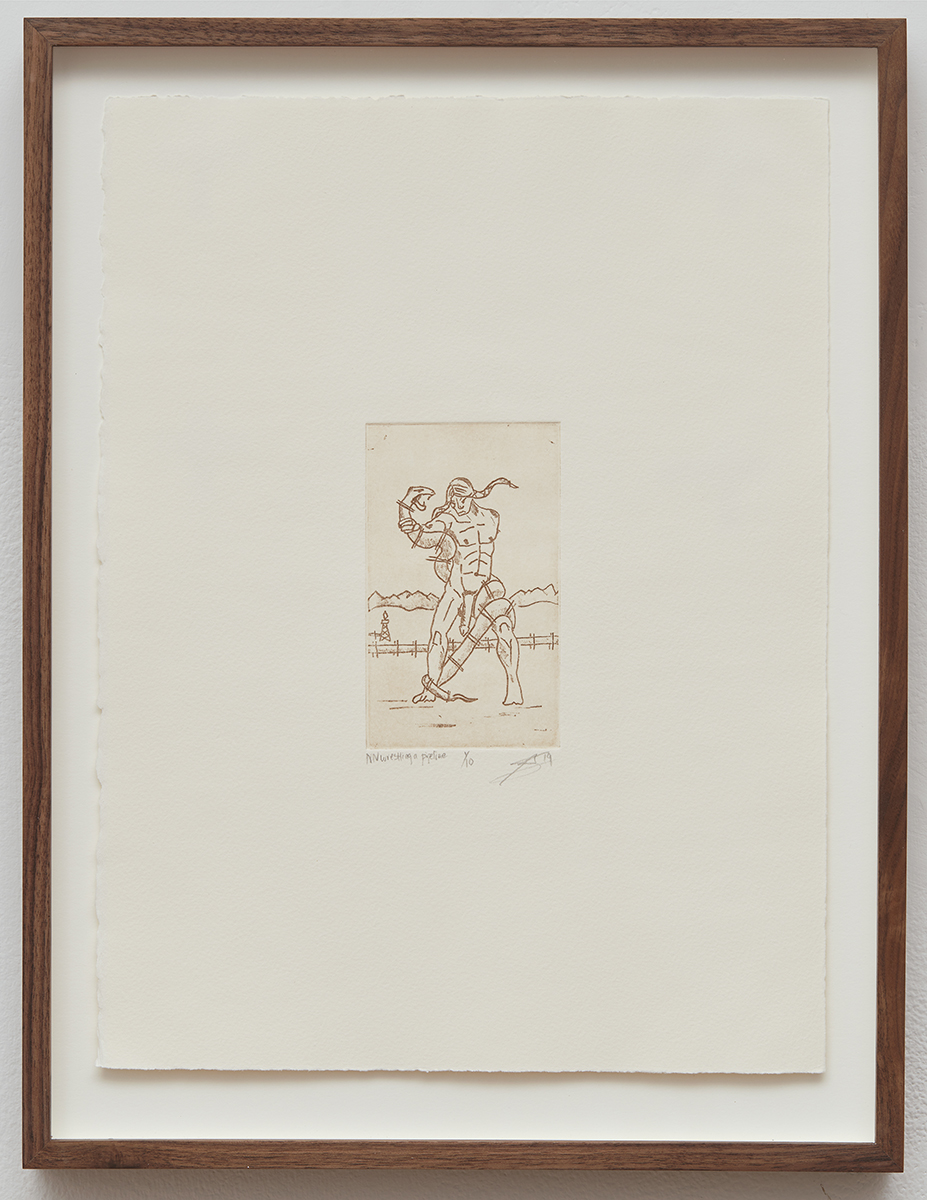

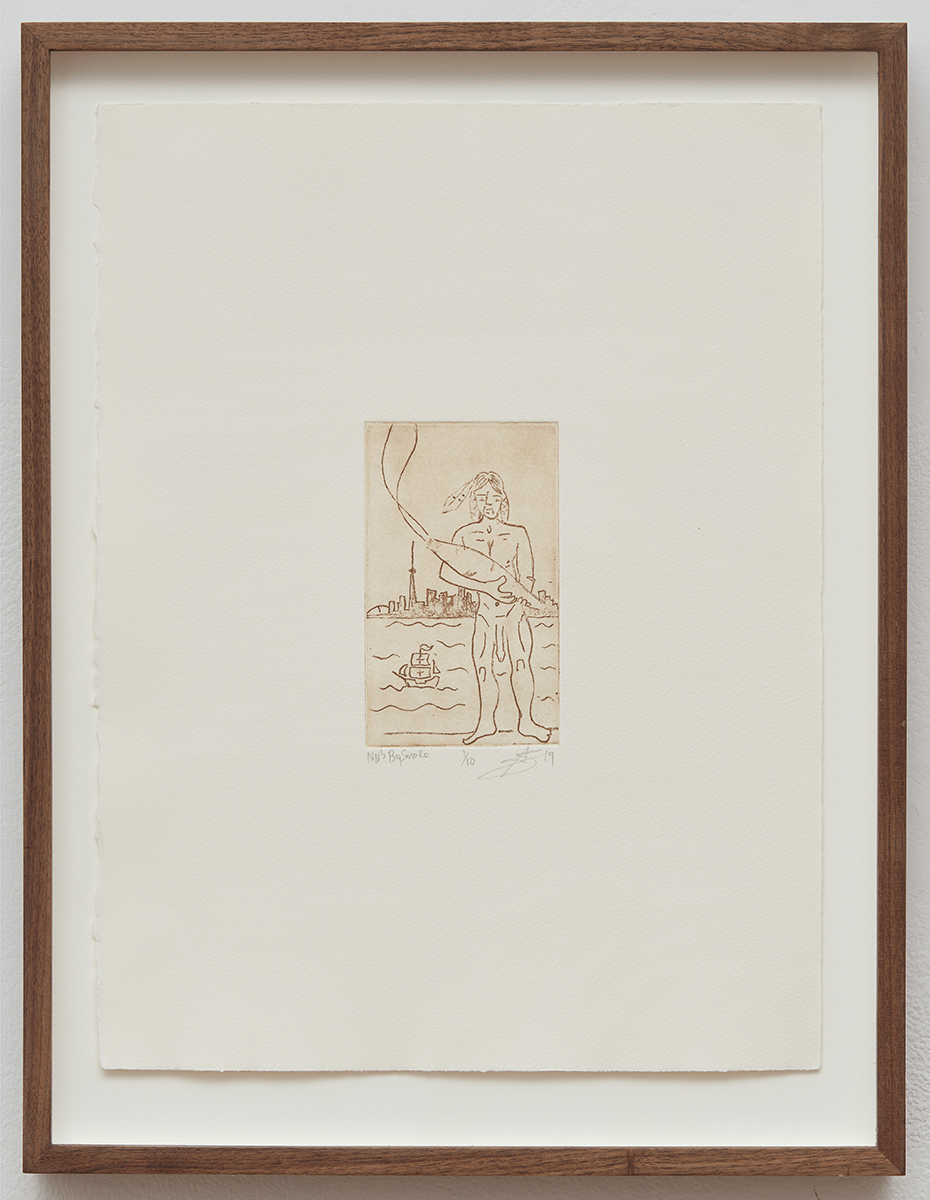

Naked Napi Big Smoke

Adrian Stimson

paintings and sculpture

June 7 - July 6, 2019

Adrian Stimson's Napi are coming east after a debut on the west coast in an exhibition at the SUM Gallery, Vancouver, in 2018 and in Edmonton at the Art Gallery of Alberta this year.

During my MFA at the University of Saskatchewan, I wrote a paper called “Too Two Spirited for you; the absence and presence of Two Spirited people in Western Culture and Media”. Part of the research was going back in history to the earliest meetings between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples to see if there were any depictions of Two Spirited people.

Of many artists Theodore De Bry stands out. De Bry who never visited the Americas, created a number of etchings for books, illustrating various meetings between conquistadors and indigenous populations as well as depictions of indigenous life. These depictions were based on first hand accounts, highly stylized and detailed and often-portrayed violent acts toward the indigenous population reinforcing the colonial conquest narrative. De Bry’s images are evidence of the diversity of sexuality in the America’s pre-contact, they prove that for the colonizers indigenous sexuality was to be feared, conquered or destroyed. Sadly as De Bry’s etchings prove, many “sodomites” were put to their death, thus pushing underground or eradicating Two Spirited being, sexuality and ceremony. Western Christian morality was not compatible with many of America’s indigenous populations, a systemic process of eradicating indigenous ways of being was put into place; Indian Wars, starvation, diseased blankets, aggressive assimilation, residential schools were some of the many racist policies implemented and continue in our times.

Historically, indigenous peoples were sexual and were not ashamed of sex or their bodies. Nudity was normal, the human body was a part of nature and in observing nature, sexuality was diverse and to be celebrated.

For the Blackfoot, a lot of our stories have sexual content, sex and sexuality was often interwoven within the language. A cultural worker friend of mine who was in charge of recording elders many years ago, told me how funny it was to translate the recordings of the elder women, she said, “it was like being in a men’s locker room”, the descriptive, unapologetic and funny use of sexuality within the language demonstrates that we were not afraid of our sexuality nor western morally, we are not bound to western ideas of piety, shame and fear of sex and sexual diversity. Yet the damage has been done and in our time, it is our right and duty to reclaim our sexual histories, I first presented Naked Napi at the SUM gallery in Vancouver, I now present Naked Napi Big Smoke in Toronto. I hope through this series of paintings to trigger people, to help them understand and accept our ways of life. To be Napi and create stories for our time and Two Spirit being.

Napi is a Blackfoot character that is central to our stories; he is often referred to as the “Old Man”. Napi comes from the sun, he is our quasi-Creator, he is crazy, funny, and is sometimes a fool. He also can be brutal and very mean. In many of our stories, Napi is the creator – along with “Old Woman”– of many of our objects and creatures. Napi is not our god, yet like many divine entities he is credited with creating the world and everything in it. But Napi also gets into a lot of trouble when he starts messing with his own creation; this is why we also refer to Napi as a trickster, a contrary. Napi stories are very familiar in Blackfoot country, often told by elders who have a history of story telling and the rights to tell these stories. Napi and his many stories are our guide to life, he teaches us lesson on how to live and not to live, in a way he is our moral guide, giving us insight into our human condition.

My intent in creating the series of paintings called Naked Napi and Naked Napi Big Smoke is to talk back to and appropriate De Bry’s depictions, especially the emasculation, degradation and slaughtering of the Two Spirits, to bring them into the present, exorcise the horrors that these Two Spirited people faced, to reclaim our power, bodies and sexuality.

While Napi Stories are often told by elders who have been the recipients of these stories from time immemorial, a new generation of Blackfoot artists, actors and story tellers have started to create new Napi stories, Napi is not static, he is dynamic. In creating these stories, I hope to reimagine Napi in the present, to Queer him, to create new stories and ideas based on our past yet reflect our present and future. As a part of creating these paintings, each painting will come with a story, a story in English, to be translated into Blackfoot. Stories that tell of moments in our time, our struggles, our hopes, both funny and tragic. Hopefully this creates a space where we can imagine a future where Napi still gives us insight into our human condition and be a continuum of Indigenous/Blackfoot knowledge.

— Adrian Stimson

Adrian Stimson was born in 1964 in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. He is a member of the Siksika Nation (Blackfoot Reserve, Alberta), and was raised there. He served as tribal councillor for eight years in the 1990s, leaving to pursue art in 1999. Stimson studied at the Alberta College of Art and Design in Calgary, Alberta, receiving his Bachelor of Fine Arts in 2003. He has since completed a Master of Fine Arts at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon.

Stimson uses a variety of media in his art that incorporate themes of history, gender, and identity. His Buffalo Boy performances use satire to critique stereotypes about Aboriginal people, his installation Old Sun explores the legacy of the residential school system, while his Transformation exhibit of paintings examines the subject of missing Aboriginal women. His work has been exhibited throughout Canada, and he is particularly known for his “tar and feather” series.

Bison often appear in Stimson's work: “I use the bison as a symbol representing the destruction of the Aboriginal way of life, but it also represents survival and cultural regeneration. The bison is central to Blackfoot being. And the bison as both icon and food source, as well as the whole history of its disappearance, is very much a part of my contemporary life” (Canadian Art Magazine, 2007). Stimson has received honours and awards including the Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal (2003), the Alberta Centennial Medal (2005), and the Blackfoot Visual Arts Award (2009). In 2006, Stimson served as artist-in-residence at the Mendel Art Gallery (Saskatoon).

In 2008, Stimson was featured in an episode of the documentary series Landscape As Muse. In 2010, he was selected to travel to Afghanistan as part of the Canadian Forces Artists program.

In 2018 Stimson became a recipient of a Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts.