Foil Problem

Sandy Plotnikoff

February 25 - March 26, 2011

Found Foils

by Amish Morrell.

Like other projects by the Toronto-based artist Sandy Plotnikoff, these recent foil-stamping works began with employing materials and tools made available to him through their obsolescence. This particular series began with an advertisement on Craigslist, posted by a leather goods shop on Toronto’s College Street that was going out of business. The shop was selling an antique foil stamping press that used metal type and dies to emboss text, such as “Made in Canada” or “100% Leather” onto its leather products with metallic foil. Plotnikoff, whose work has also employed materials including monochromatic sweatshirts gleaned from used clothing stores, snap fasteners, Velcro, second hand belts, and used socks,typically begins by finding a material that has become cheaply and readily available as it has fallen out of commercial or practical use. Over time working with a given material – more than seven years in the case of the foil-based works – he pushes it to the limits of its material possibility, while also enacting an alternative system for its dissemination.

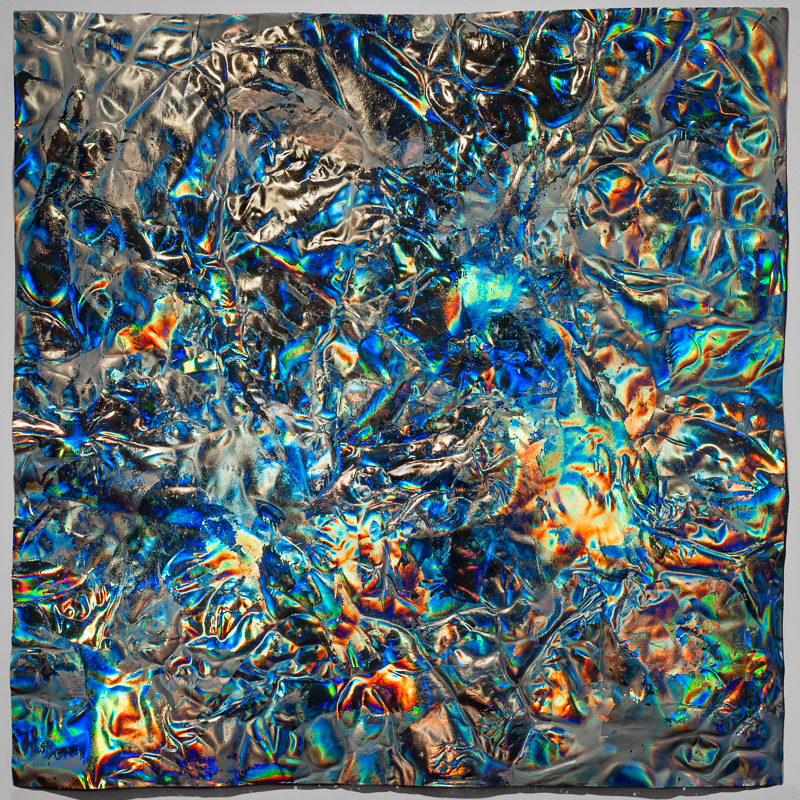

While many people might not know what foil-stamping is, based on the term used to describe this process, foil-stamped lettering is immediately recognizable. It has been a ubiquitous part of consumer and advertising culture over the last hundred years, used on book covers, day planners, stationery, pencils, clothing, shoes, accessories, passports, credit cards, currency, lottery tickets, award ribbons, trophies, cosmetics, matchbooks, wine labels, chocolate bar wrappers and endless other product packaging. Despite being bright, colourful, and highly reflective, this material is dispersed almost invisibly throughout the world of objects, disguised within it’s printed surfaces of text, graphics, and security features, such as the holographic images used on id, credit cards, and currency. The visual quality of the foil is occluded by its function and the meaning of the text it has been used to render.

But it takes a major shift in context, and in legibility for it to become so visible that one doubts how one could ever have missed it. As part of an ongoing series, Plotnikoff prints onto vintage postcards the names of places that clearly are not the places depicted. Here, the discrepancy between the text and its context draws attention to the gesture itself. The vintage postcard is already outdated, and the juxtaposition creates a rupture between the image and the reality it is intended to represent. That series evolved into increasingly abstract foil treatments on the postcards that would transform and often obliterate the image itself. Plotnikoff has since expanded these abstractions into much larger works on paper with no background image, instead working off a primed surface of matte black copy toner. These prints are his current body of work, titled “Foil Problem”.

Second hand stores have been a major source of material in Plotnikoff’s practice for several years. He has made various works that specifically engage the thrift store as a textual and graphic pun, as a model and resource for studio practice, and as a system for questioning value and facilitating social exchange. Part of this process involved foil-printing thousands of hand-made Value Village price stickers, and applying them to different objects, revaluing them in strategic ways. For an earlier work, he altered clothing purchased at thrift stores by adding extra legs onto pants, sewing tennis balls inside shirt pockets, stapling socks into backpacks, and various other surprise interventions, before donating them back directly into the racks at the store, so that they re-circulate as an anonymous sculptural work within the second-hand economy of the thrift shop. For a sculpture course that he taught at the University of Guelph, the class had after-hours access to a nearby thrift store as its classroom and studio, with students creating work and installations using the materials available onsite.

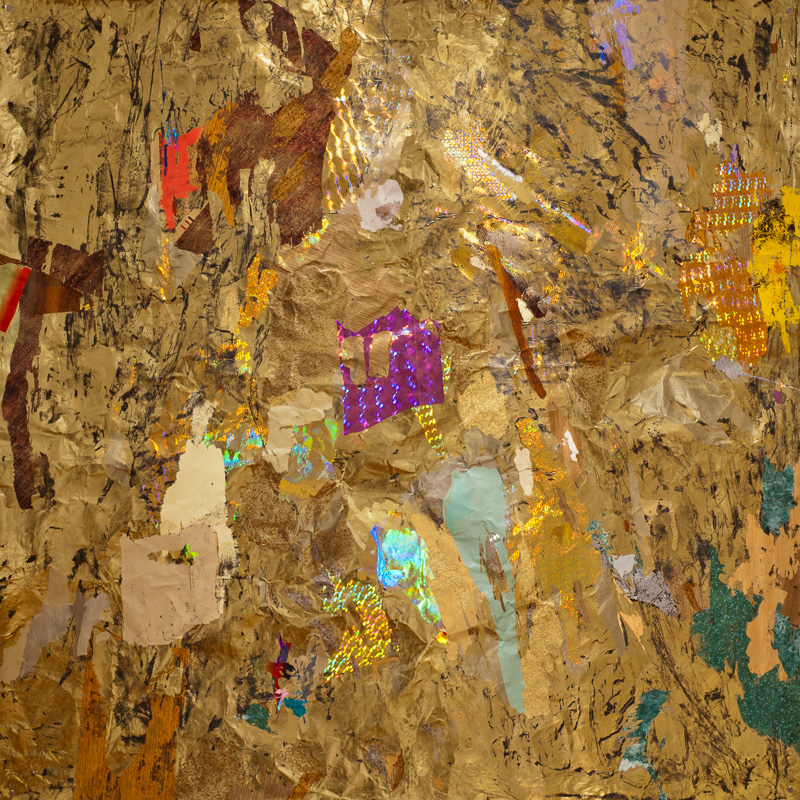

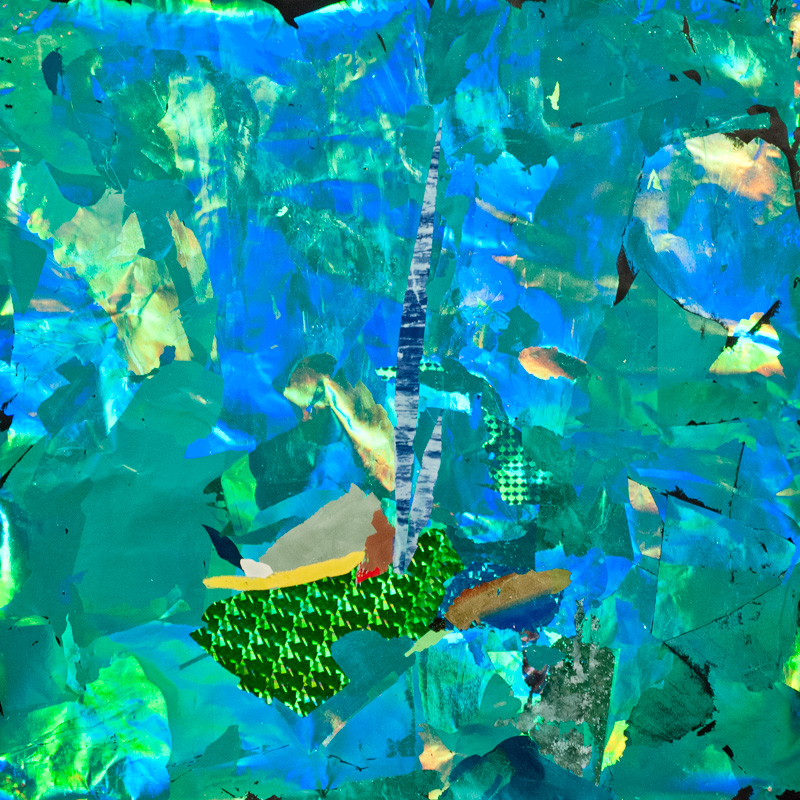

Plotnikoff’s work reflects a strategic engagement with everyday material, and alternative systems of dissemination. Many of his earlier foil works were printed directly onto found or in-use items such as cd jackets, books, stickers, postcards, food, napkins, coins, wallets, clothing, furniture, jewelry, bread clips – effectively any and all possible surfaces foil will print on – where the work has often retained a semblance of textual meaning or utilitarian function. And here, many of his more abstract compositions were made using the remains of foils from other projects, sampling and recombining elements of those found texts and graphics. "Foil Problem", however, offers a new level of abstraction, with none of these textual references. Instead the references here are purely textural, playing formal qualities from diffraction patterns, holographic smears, wood grains, faux marbles, pastel tints, and brightly-coloured pigment foils against a flat matte black background. Light is reflected through the prismatic layers of foil, becoming at once painterly and sculptural. This cacophonous distillation of discarded material works appropriately on gallery walls.

This is an important turn, for work that previously might have been seen as finding its critical purchase in the everyday, rather than in art history. Here it also condenses a number of concerns of earlier movements within modernism. Photographers including Alvin Langdon Coburn exposed photographic paper by shining light through prisms, and thus explored how machines could produce images automatically. Brassaï photographed objects such as a roll of bread or a bus ticket, creating what he called involuntary sculptures, where ordinary objects seemed unsettlingly perverse. In a similar way, Foil Problem reveals the dazzling opticality of a material detached from its everyday commercial uses. Except that instead of looking forward, into a future of speed and machines as did the Futurists, the Surrealists, and the Suprematists, Plotnikoff is looking backwards, to these same earlier technologies, and showing us something we haven’t seen yet.

- adapted from a text originally printed in Hunter and Cook, Vol. 6. May 2010