What Is Wonderful World?

Sadko Hadžihasanović

March 11 - April 7, 2006

Sadko Hadzihasanovic in conversation with Robert Enright

Q. Has this most recent body of work been gathered together specifically for the show at Paul Petro Contemporary, or had you been you working at it before?

A. I started on this body of work a year ago in March. I was in Slovenija and I had a solo exhibition there after 20 years which included one painting I'd produced in 2004 for the Yugoslav Biennial of Young Artists in Vrsac, Serbia. The Biennial was for new media and so I wanted to do something different. Also there was one artist to whom I wanted to do a homage, his name is Gabriel Stupica and he was a very important artist in Yugoslavia. He was like Philip Guston in that he broke at a certain point in his career with the intimate still life work he had been doing and he started to do white paintings with lots of cartoon elements and collage. He was one of the most influential artists for me from the time I started doing art. So for the Biennial I did an homage to Stupica who is a Slovenian artist, which was interesting because the show was in Serbia and Serbia is now completely separate from Slovenija. I tried to connect a little of that history because Stupica still has two big paintings in the Museum of Modern Art in Belgrade. His work employed a lot of white on white and self-portraiture was also a big subject for him for a long time. So I produced a very similar painting as an homage and although I was not impressed with the exhibition in Serbia - it was a bad set up or something - I got an invitation to exhibit the painting in Slovenija, Stupica's home country. It was in February of last year and when I saw the painting on a white wall it struck me that I had to do more paintings like it. So I came back to Toronto and started the new works.

Q. A lot of these new paintings take place on a beach.

A. I have two bodies of work in the show. On the ground floor are huge, 10 x 8 feet images of children, and I call that group Playground. That was the group of paintings I started to work on immediately after I came back from Ljubijana. It was a continuation in my interest in images of children, in popular culture and of my fascination with North American culture, But what was new was that for the first time I did paintings on canvas in a big size. Before that I had worked on wallpaper.

Q. But Welcome to the Playground still has a segment of wallpaper in it?

A. Yes. I wanted to bring back a hint of that but it was a new process because wallpaper itself is a readymade background and you don't need to fill it in with big strokes and lots of paint.You just do your drawing and add little bits of collage. The wallpaper keeps the pigment on the surface which means that I can work quickly and you can't do that with raw canvas. I started only drawing in charcoal on raw canvas and instead of priming the canvas, I also started to paint at the same time and it was a completely new surface and texture, which I especially liked.

Q. The Gameboy painting, among others, indicates that you continue to draw your imagery from popular culture, from newspapers and magazines?

A. In these paintings I am using children that I know. In Back to School it was my cousin and my daughter, who I just asked to pose because I knew what I wanted to get. But the things around them call on popular culture. So in Welcome to the Playground on the right hand corner I put a reference to Pepsi. Also if you examine the boy closely in Back to School he is wearing Rayban glasses, very cool things in Europe, and his T-shirt has the sign of a very popular group called Queens of the Stone Age, and he is wearing army pants and has a cigarette in his hand. Everything is a mix of what could be considered cool and not cool. I also started to bring in elements from Eastern Europe, like the title of the painting Welcome to the Playground, but I wanted to get the feeling that you don't exactly know where the place is: it could be in Russia, it could be in Yugoslavia, and it could also be Canada. I like that mix and that criss-crossing between cultures because I don't think there is a separate place where you can say "this is exactly this country". My idea is that you are always a little confused. There are other quotations that come from the history of painting, or from mythology or from elsewhere. The two boys fighting in Welcome to the Playground can be Abel and Cain and they have stopped and they're posing. It's the same thing with the boy in Back to School, it's not real fighting , everything is mixed between real life and tv and movie life. The boundary between them has dissolved or has become soft. There is also a small drawing of the cat from the Shrek movie, whose voice was done by Antonio Banderas, and because I have done self-portraits as Banderas, it was a way of including myself by using somebody else as a stand-in. I also put in the skull which I like very much from the history of painting.

Q. The skull is a classic memento mori device isn't it, a reminder of death and a caution against vanity?

A. Yes, but it's also a symbol that has resonance for an artist from Bosnia. There is one other thing about the Playground Paintings that I should mention. I deliberately did them very big as a reaction to the gallery situation on Queen Street West where you have small venues and small works being exhibited. I wanted to do something completely opposite and go with huge paintings. Three of them are 8 x 10 feet and the other one is 90 x 60 inches. I have more but there was no room for them.

Q. What about the upstairs space in the gallery?

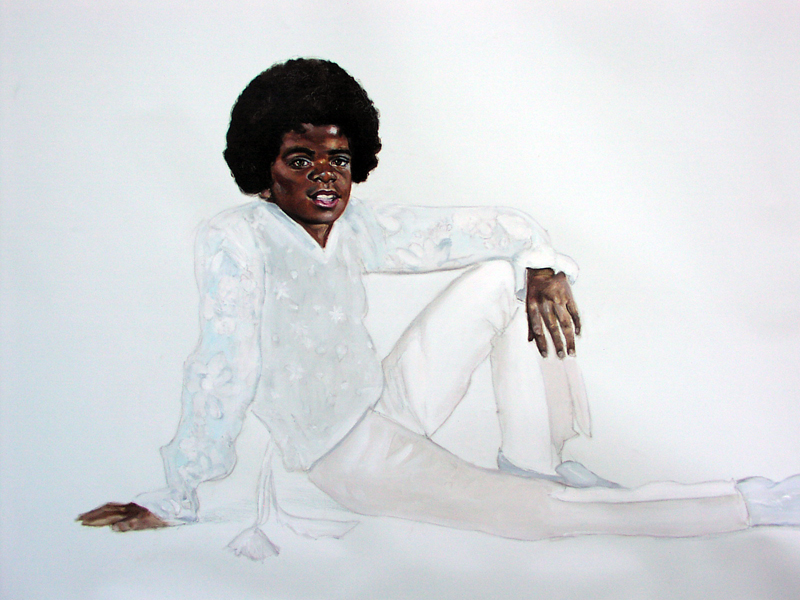

A. I'm putting a group of works which I started to do three months ago. They're portraits of people who have been wrongfully convicted. In one way this work is a continuation of the portraiture I've been doing: the missing children, 50 Most Beautiful Guys, the People magazine work, and I wanted to go off into this new territory. So far I've produced five paintings (they're 36 x 36 inches). I didn't just do their faces which was my initial intention. I decided to put them in places they have never been, so I set up beaches that are stages, like in Cuba or anywhere in the South. They stand there looking into the distance, into space that, even though it looks recognizable, is mostly unreal, like a theatre stage. I wanted to do it in a realistic way but something happened that makes them not belong to the background space. I also included other elements, like cartooning. There is in one piece, the one with William Mullins Johnson, where I put Shrek and his partner sitting on the beach. Johnson was the babysitter who was convicted of killing the young girl under his care. He was accused and years later he was freed.

Q. Why is the character from Shrek 2 on the beach?

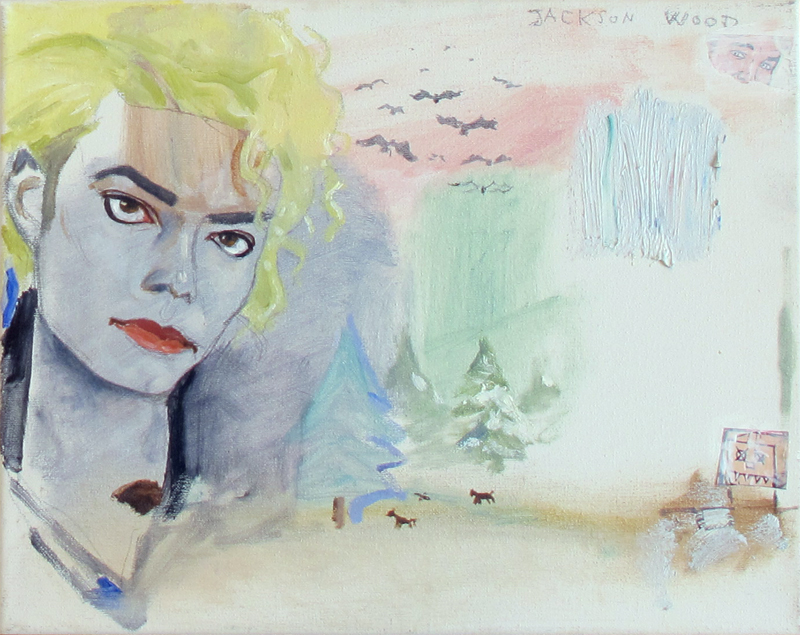

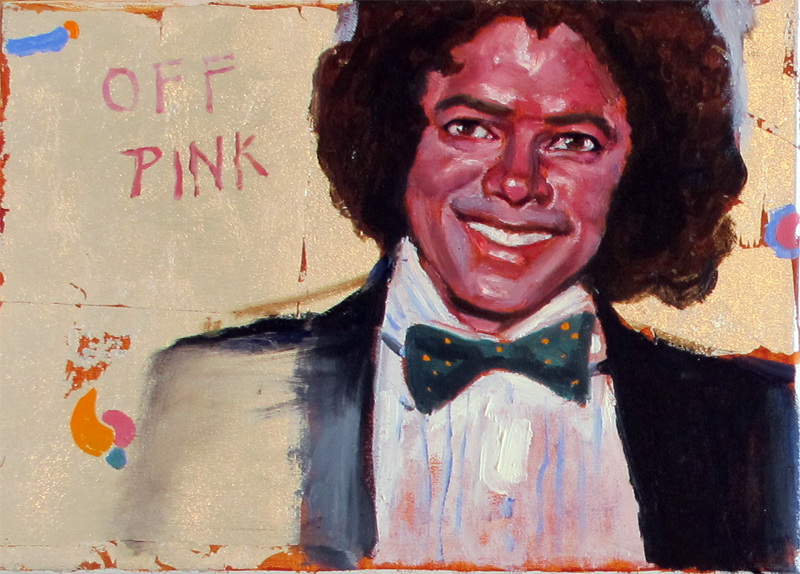

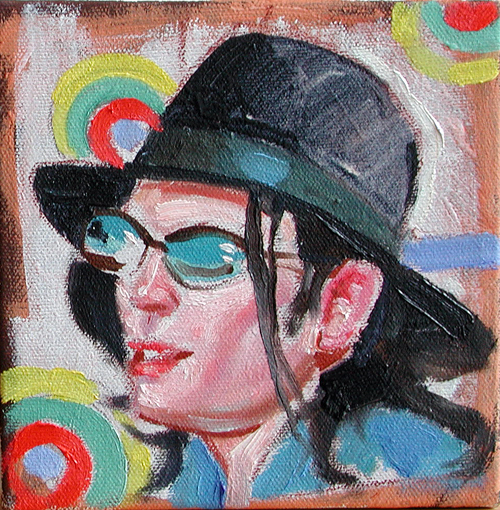

A. I like the idea of mixing cartooning with the real. For me it creates a slightly surrealistic feeling which I wanted. I want things which give energy to the painting and that can be read in different ways. Those elements also make the place unreal. The painting with Robert Baltovich does the same thing with Cubawood in the background. He was accused of killing his girlfriend but now they think she was a victim of Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka. He's not entirely free, the process is ongoing. But that corresponds to my idea of not deciding whether anyone is innocent or not, but to look at what happens to people who are placed in circumstances where they could spend their entire life in jail. They become like lost souls. One of the women, Louise Reynolds, was accused of killing her daughter and she lost her house and job, she spent two years in jail and after that they proved that a dog had come into the basement and killed the girl. She is now in then process of suing for seven million dollars. Another one of the wrongfully accused is Steven Truscott. But I only had faces of these men, so when I was in Cuba the last time I asked my wife to take photos of my body in different poses. When I started to work on the project I just put their heads on my body. It wasn't that I especially wanted to put myself in the work, but it was the only source I had for making bodies for them. I'm thinking about calling the series Places They Have Never Been. I'm only half way into the series and I'm not exactly sure why I put some things together with other things. I have a general concept for each painting but I like to keep an open way of reading things. I think it's a good thing to not only use intellect and logic to make decisions, but to use the unconscious as a way of contributing to the meaning of the work. I should say, too, that there are also a few paintings of Michael Jackson and I use them to connect what is happening in the upstairs and downstairs space. One painting is Michael Jackson and the Saudi Arabian king and I call it What the Wonderful World. He connects things for me because in the popular imagination he has something to do with child pornography. I don't want to accuse him but you have people upstairs who are wrongly accused and it seems like he belongs in between the paintings of children and the wrongly accused.

Q. So he walks the line between the two bodies of work? What the Wonderful World is a wonderfully ironic title.

A. Yes, it's ironic, just as Playground is ironic. Also think how what the wonderful world applies to the wrongly accused. I did another painting called Off Pink, which I painted from a photograph of Michael jackson before all the cosmetic surgey, when he was brown. I produced these works last month and they weren't planned for the show but when I saw the photo in Rolling Stone magazine I realized I could use him to connect the two bodies of work.

Q. Are all these paintings oil on canvas?

A. Only the first coat of the paint. On the bottom of the beaches there is transparent acrylic diluted in water. I cover all the painting and after that for the landscape and for the flesh I use only oil. I couldn't see the flesh without oil. I remember an interview you did in Border Crossings with Cecily Brown where she says that oil was invented for the flesh. I agree with that.

Q. These works have a strong element of drawing and I wonder if that changes how you characterize them?

A. I'm balancing between the representational and the surrealistic, a little bit like de Chirico. I find that to refresh myself I have to go outside of the visual langauge I'm used to and then come back to it. That was why I did watercolours and now that I've come back to oil painting I find that I've become less perfected. Five or six years ago I was showing more skill, showing how well I could paint. I found that in the oil painting and mixed media I'm not trying to show how to paint well technically but to use technique to paint a little awkwardly and illogical and to show the process more.

Q. In Back to School I notice that the young woman's hand is painted with very strong marks that look like drawing and yet her face is rendered very painterly, with close-valued flesh tones. Do you think of these as combinations of drawing and painting?

A. That is what I have wanted to do throughout my 20 year career: to combine drawing and painting. In the Wallpaper work I was more successful because if you draw on canvas it doesn't look so good - it appears empty and flat - but if you draw and paint on wallpaper it looks immediately strong. In this work I was looking to have strong surface in the painting and to have freshness and spontaneity in the drawing. That is why you see that intersection between strong flesh in the portrait and then that hand which is just lying there, like Egon Schiele, and then the red paint which slowly disappears again into drawing. I want to find a visual language where I can balance line and form. When a friend asked me who I would want to be closest to among the painters I admire, I realized it was Matisse. Not in his simplification but in how he established a relationship between the decorative and the three-dimensional. That was what was successful about my Wallpaper work, I had the flat decorative wallpaper and the figurative drawing on top of that, so you have this tension between flatness and figurative representation.

Q. When I look at a piece like Welcome to the Playground, I can't help but think of Larry Rivers.

A. Yes, but I didn't know about him when I started to develop my visual language in the painting. He was American and we didn't have a chance to see many books. But I see some similarity because he has also included text and some parts are finished and other parts are unfinished. But I have more collage than he does and that came from Gabriel Stupica. I like collage because it was a very helpful way in art school to bring together traditional and innovative things. Putting things together in small collages would often give me ideas about what I could do in the painting. Also collage is such a fine way of introducing new visual elements into the work. So the boy playing guitar in Back to School recalls the way that Picasso used the guitar in his cubist work. So it's about my knowledge of the history of painting, for which I care very much, plus the innovative quality of collage.

Q. Take me through the way you composed a work like Back to School?

A. The boy and girl was one photo and that was my starting point. But I always have lots of other things on the wall in the studio and I have a photo of a boy from some medieval class my daughter had at school and I also took that photo. After that I put in the disco ball because it reminded me of music, which the guitar player had already introduced, and then I put in the Corona beer bottle. In Playground I had only the idea of the two boys fighting. Also there is the faint figure in the background from Shrek which was playing in the cinema at the time. When I'm painting I also have lots of magazines around, like Rolling Stone, and I put different sentences from it into the work, or a political text, or some music, just to see how it works visually.

Q. So you're making these decisions as you go? You don't have a template from which you're working?

A. No. I have a rough idea but many things come into the painting. They just happen in the process of painting. I use collage mostly in the beginning. There is a collage in Back to School where I put two photos together, and in Gameboy I have Hanna and another girl. Some of it has to do with surrealism as well, with the idea of putting things together to see what happens if they collide.

Q. But it's a kind of Pop Surrealism rather than being standard surrealism?

A. I like that description. Because I don't want to be deep in meaning. I want to show how Pop culture takes everything from any source. I must admit that sometimes I am surprised by what happens in these combinations. There are many smaller stories circulating around the main story and so you have to pay close attention to the surface.

Q. I often think that for you the white spaces are as important as the spaces that are filled in?

A. It's of great importance to me. Sometimes I care more for what is around the figure than the figure itself. Every inch is so important. John Brown says that a painting should look good from 10 metres and from two centimetres. You don't get that so often in Toronto, even with artists who have good careers. I think of Leon Golub. I wasn't taken by his concept of violence but when I saw his painting from close up, I realized how innovative he was. Everything, from how he scratched and worked the surface, impressed me and I realized those are the things that will keep him in the history of painting.

Q. Do you think of the paintings as having points of entry? You have central figures but they're not necessarily centrally located in the composition. Then there are these other things that orbit around them, although orbit may be too organized a term. When the viewer looks at a work, how do you expect them to read it? I guess it's a question of the strategy of perception.

A. That is what I learned when I came to North America. There are other smaller stories and they are also part of the painting language. What I realized when I came to Canada was that people take five seconds to read a piece in the gallery and because in North America the rooms are bigger you have to have something big to hit the audience with. That became my strategy.

Q. What's with the banana in Hanna in Artist's Studio? It seems to determine the tilt of her head. The thing that is least meticulous in its realisation plays a disproportionate role in the composition itself?

A. It was just a visual reason. I needed to put it in to hold the painting together. I might have come to the banana because of Warhol and the Velvet Underground. It could be because music plays a big part in my art. I put a small reproduction of a Velvet Underground painting in the composition as well. Some images just pop in when you least expect it and you don't know why. My way of staying contemporary is to follow what is around me. That was what made me survive as a painter when I came to Canada. When I changed subjects, when I became ironical, used humour and commented on contemporary life in Canada and in North America, that's when I became part of the contemporary painting movement.

This interview was conducted on March 2, 2006. Robert Enright is the Senior Contributing Editor to Border Crossings magazine and the University Research Chair in Art Criticism in the School of Fine Art and Music at the University of Guelph. In September of last year, Mr. Enright was made a Member of the Order of Canada.